Monthly Posts: November

Can FinTP turn 2014 into an open source milestone?

This is not meant as a mini history of open source important moments, but as a reminder that not all bold ideas are necessarily crazy ones.

1983 – Richard Stallman starts the GNU Project, a mass collaboration project for open and free software that has resulted in a huge amount of open source software over time and gave birth to the GNU General Public License (GPL), arguably the most popular open source license model out there.

1991 – Linus Torvalds creates Linux. Pretty sure this moment in time does not need any more explanations. Anyway, the Linux kernel became the last piece of the puzzle for the GNU operating system project, providing an entirely free and open source operating system.

1993 – Red Had is founded. The company, based around its own Linux distribution, made open source big business, proving that it was possible to be highly profitable with something that is, at its core, free and raising the profile of open source significantly over the years.

1994 – Development starts on MySQL. After the first version was released in 1995, MySQL has become over the years, the open source database solution of choice and is used by a huge number of companies and websites like Facebook and Wikipedia.

1995 – The first version of Postgres is released, following a project meant to break new ground in database concepts such as exploration of “object relational” technologies. Nowadays, PostgreSQL, name given starting version 6.0 to reflect its support for SQL, has a user base larger than ever that includes a sizeable group of large corporations who use it in demanding environments.

1996 – Apache takes over the Web, showing how an open source product can come to almost completely dominate a market. Ever since 1996, Apache has consistently been the most widely used web server software on the Internet.

1998 – Netscape open sources its web browser. Together with that, it started the open source community Mozilla to hold the reigns. Although Netscape eventually faded into obscurity, without their historic move there would have been no Mozilla, and without Mozilla there would have been no Firefox.

1999 – OpenOffice is launched. In August 1999, Sun Microsystems released the StarOffice office suite as free software under the GNU Lesser General Public License. The free-software version was renamed OpenOffice and coexisted with StarOffice.

2004 – Canonical, South African Mark Shuttleworth’s company, releases Ubuntu. Few could have predicted what a massive success it would become, as Ubuntu quickly became the most widely used Linux distribution by far, especially on the desktop, and has brought Linux to the masses like no other distribution.

2008 – Google releases the first version of Android. The new smartphone operating system released in September, as open source is based on the Linux kernel. And that’s how Linux has become the dominant kernel on both mobile platforms (due to Android) and on supercomputers, and a key player in server operating systems too.

2014 – Allevo launches the first open source application for financial transactions processing, dubbed FinTP. Following the decision to change its business model, the Romanian company publishes, under free-open licensing terms, the code of its own financial transactions processing engine, a solution that gained a lot of reputation for Allevo on the local financial market.

Indeed, at first sight, the Allevo move lacks the glamour of “worldwideness”. Hence, the question: can FinTP really turn 2014 into an open source milestone? Honestly, I don’t know how to answer this question. But I do believe that it has the potential to shake a few rocks in the banking and financial industry, an industry maybe too conservative if we were to take a peak in other industries and analyze their pace of change. And yes, it has the potential to change the status-quo.

It’s only natural that we can’t expect the boom of Linux or MySQL in FinTP’s case, even if only because FinTP addresses a really narrower market niche. But we can imagine that this small step for open source can become a big step for the financial market.

For the circumspect “there is no harm in trying” is never enough. And it shouldn’t be. But it is also true that you don’t know what you’re missing until you try it. And that’s exactly what is fabulous about open source, even for the nonbelievers: even if you are just curious, you can have a bite without buying the whole pie. You can browse around the code – it’s open, isn’t it? -, you can join communities and talk freely with other curious or passionate. And all, as transparent as it gets.

Maybe that’s all that FinTP needs at first: just a little bit of curiosity. Just enough to make us try it and then decide for ourselves.

Quick exercise: translate the binary code from the image on top of this post. What does FinTP say?

Scaling in the Real World

rich guy with friends

Imagine you are a rich farmer in the middle ages. Life is good and even though you have the most land to plough, you’re always the first to plant the seeds, because your loyal oxen do the hard work for you.

Now, not everybody is that lucky. Your neighbours are still using their bare hands and feet and working all day in the heat is wearing them down.

Being such a good neighbour, you decide to help them and offer your oxen as a service and now everyone is winning: they get more land prepared for crops and you collect a small fee for lending them the oxen.

Scaling

The business is going well and now the villagers are queueing at your door for a time slice with your beasts.

Would you replace your ox with a bigger one to get more work done? Sure, it will work for a while, but oxen can only get that big, right?

In application architecture, this approach is called scaling up. As processing demand increases, you add more resources to your server or even replace it with a better one.

Scaling out is another approach to application scaling. More servers are added to meet an increase in processing demand and work is split among them.

Not all applications can scale both ways. Scaling out works for applications that can split work into independent subtasks, while scaling up works for applications that have to perform related tasks.

Adding more oxen allows you to plough more fields at the same time, while having the fastest ox allows you to finish a field faster. Ideally, you’d want to have more fast oxen.

Costs

Scaling up has the benefits of low maintenance costs because the application never gets touched.

Administrative tasks are simple: any upgrades or patches for your application or the infrastructure (OS, servers) get deployed to a single instance and errors are investigated in a single place. You really love your admins, right?

Hardware costs may, however, get prohibitive. It’s easy to add more memory or CPUs when slots are available, but after a while you’ll have to start replacing parts and throwing away the old ones. Some components don’t support mix and match, so you have to replace them all at once.

Then there’s the snowballing effect: more CPU leads to more power needed, better cooling is required and the operational costs only go up.

Scaling out allows you to keep using old components. New servers are added on demand and servers are spin off when the peak of demand passed, eliminating wasted energy.

Efficiency

Let’s consider just three resources that can be improved: CPU, RAM and HDD. Any increase in the three resources translates to some benefit for your application, but the challenge is to make your application scale effectively.

In order to take advantage of additional CPUs or cores, your application needs to be able to split the tasks it performs in similar subtasks that can be performed in parallel. CPU frequency only benefits applications that are CPU bound (compute intensive) such as signal processing, movie compression or chess AI.

An increase in RAM size benefits applications that handle large amounts of data at the same time, but has little impact when only small data is involved.

Hard drives speed and raid configurations impact applications that make frequent data reads/writes to a persistent medium, such as database servers.

While considering scaling up, you should also look at the way your infrastructure scales up. Some operating systems or servers are restricted to a number of processors/amount of RAM and, after all, it’s not enough to add more memory if your application can’t access it.

Single point of failure

I’m coming back to the ploughing analogy with sad news: one of your oxen just died and the other one can’t handle the yoke alone. How do you make sure your oxen live forever?

This is probably the most important aspect of a critical enterprise application: stability. If your application crashed, it makes little importance how fast the server is or how much RAM it has.

I can’t name from the top of my head an application that never crashed. Even if it was the OS crashing and dragging the application with it or bugs in the application itself, software uptime is never 100%, but still, strategies need to be in place to cope with it.

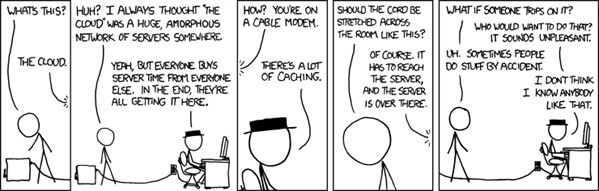

image courtesy of xkcd

The strategy I found to be the most effective is to embrace the crashes. Count on them to happen and make sure your application crashes gracefully. No work should be left in limbo, no other system functions should be disrupted and enough information to diagnose the crash should be persisted.

Downtime doesn’t have to be related to crashes, but can also be an effect of application maintenance and in a scale out scenario servers can be taken offline and serviced as required, without disrupting the whole application.

In the next posts I’ll look more into how we approached scaling up and out with FinTP and also crash recovery strategies.

by Horia Beschea